AJ and Lenny Laird joined the team for color-banding murres on Duck Island this summer. Thank you both for your incredible help in the field and for sharing this trip through your descriptions and AJ’s exquisite field-sketches (below).

And, thank you to Hamish Laird for capturing the beauty of Duck Island and these amazing birds in this video of the murre-banding field work.

Common Murres nest in colonies for safety: a large group has many eyes looking out for danger, and if one bird spots a danger it can warn the others. On Duck Island, a tiny, crumbling haven for murres, puffins, and kittiwakes on the west side of Cook Inlet, there is a long-term murre banding project run by biologists from the USGS Alaska Science Center and Auk Ecological Consulting

The murre banding project brought us to Duck Island for five days this August. Ann, a scientist who has done bird research on the island since the 90’s, was leading the field work. We – Lenny and AJ – came along as volunteers, helping to catch, sample and band the murres. Murres come back to the same nest site each year, and so banding individuals with a unique combination of color bands on their leg and then resighting these birds in subsequent years is a great way to study adult survival. This information is especially important given the large murre die-offs during the extreme heat wave in the North Pacific between 2014-2016.

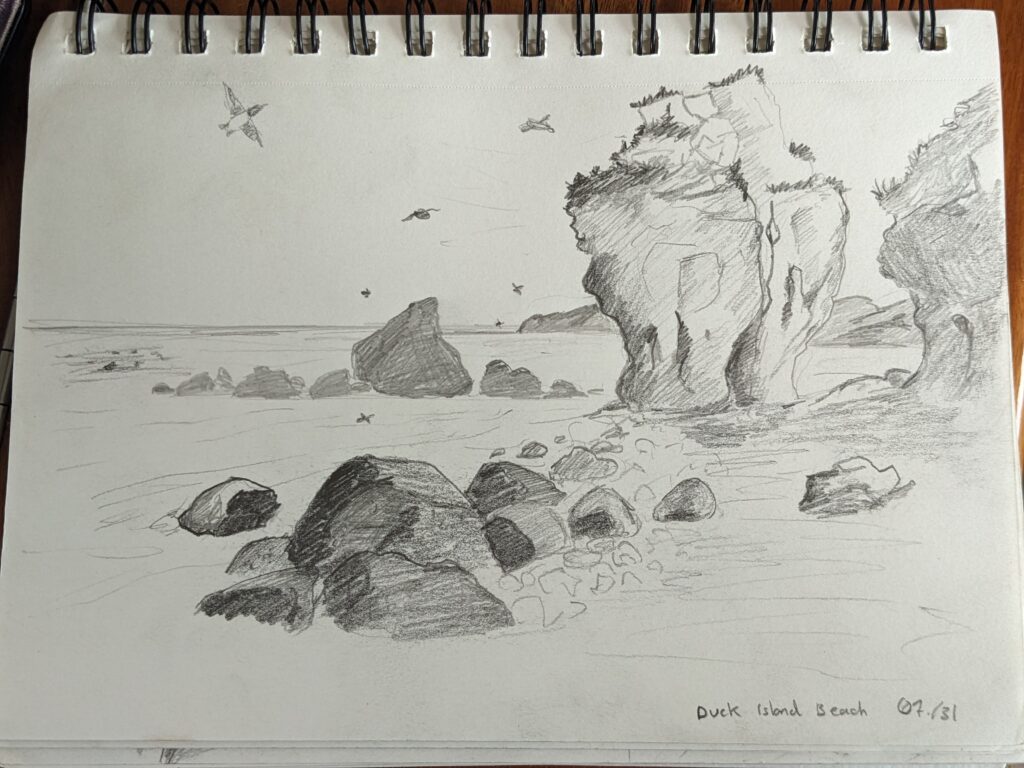

Duck Island is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, and is in itself a sort of tiny world. It is about a quarter of a mile long, and is made up of layers of crumbling sedimentary rock, leaning out of the ocean at an angle. At high tide, it looks like a shrubby ocean rock. At low tide, the island nearly doubles in size, with a wide, flat, rocky beach. On the north side, the beach is made up of boulders, on the south, there is a curving sandy beach, and a towering sea stack, narrow at the base, and orange with lichen.

The folds of sediment in the cliffs, the boulders on the beach, and the rockfalls down the side of the island, make ideal habitat for nesting puffins. You can hear the chicks peeping when you climb along the rocks on the beach. On the western side of the island, common murres nest up in the high cliffs. Unusually, the murres also nest under the thick alder trees and elderberry bushes on the top western side of the island. Alder grows all over the top of the island, making a complete canopy in some places, and this provides breeding murres incredible protection from avian predators such as gulls.

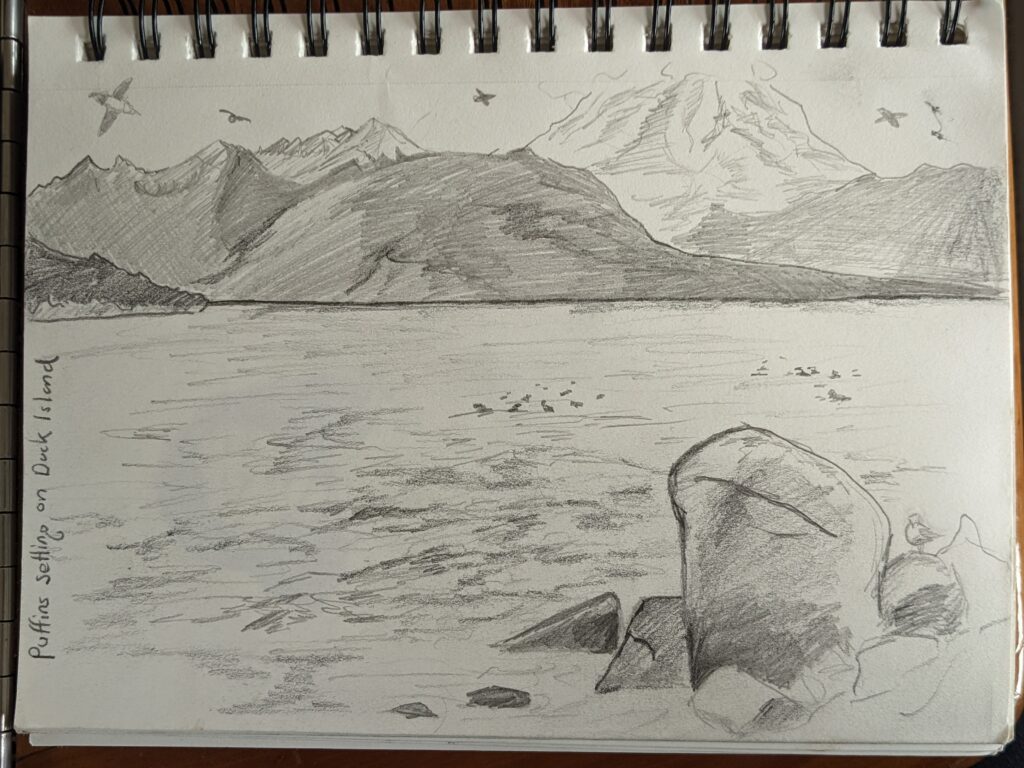

We arrived on Duck Island in the pouring rain, coming around from Tuxedni channel where Ann, who has been coming to work with seabirds on Duck Island since the nineties, has a fish camp with her family. We came across in their set netting skiff, along with Ann’s family who came to help us offload our camping supplies. They helped us lug our provisions up the beach, up the cliff, and along the narrow path through the alders. The first day we set up camp in thick black mud, but the alders kept the worst of the rain off of us. Puffins filled the water and the air, and lined the cliffs.

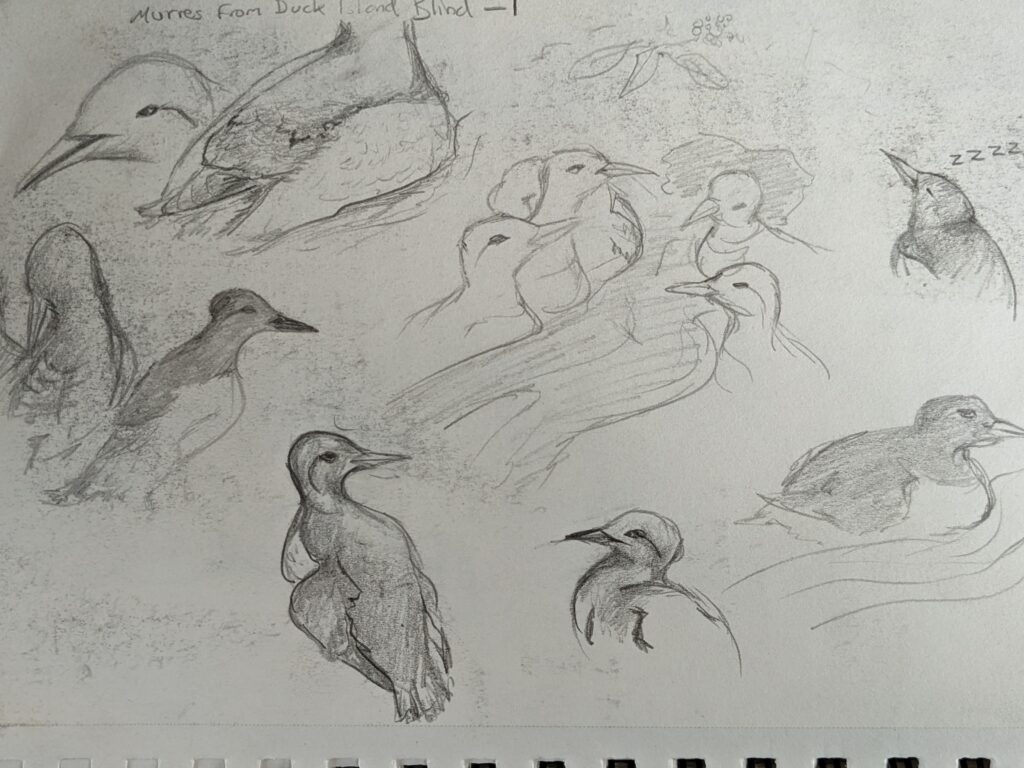

Over the next five days, we banded fifty-five murres from two sites. Murres, frequently targeted by predators, such as eagles, gulls, and even bears, are sensitive to human presence, and the main challenge in banding was letting the parents incubate and hatch their single egg without disturbance. Our visit coincided with hatching, and as the days went on the calls of the adult birds from the colony began to be interspersed with the peeps of chicks. The blind, set up earlier in the year by Ann and her son Leif, allowed us to watch murre behavior up close. Mates, trading off time incubating the egg, might sit and preen each other for a while. Neighbors might get into repeated squabbles; one murre, band ID OGO (bands orange over green over orange), kept poking its neighboring murre with a muddy stick, until the other murre lost patience and yanked the stick away!

Whenever we were near the colony we would listen carefully: too much movement or noise from either us or the call from a patrolling gull overhead would bring a stop to the constant jabbering of a relaxed colony and a low murmuring would spread through the group of birds. The goal was to keep the birds as relaxed as possible while capturing, banding, and then releasing them, so we set up our equipment in a clearing hidden behind a blind with sheets of camouflage strung between the trees on either side.

The process of capturing the first murre was amazing to watch: because we couldn’t let the birds see us, Ann used a telescoping pole with a plastic noose on one end to catch each bird, pushing the pole through the camouflage netting and maneuvering it until the noose dropped over the bird’s head. Murres are extremely strong, with neck muscles used to diving into the water at high speed, so this does not hurt them. The other birds didn’t seem to notice anything was wrong; the most they reacted was pecking or calling at the captured bird as it was pulled towards the netting, seeming to think it was walking through their territory deliberately. Once the murre reached the base of the netting, Ann maneuvered it out of the noose and into a waiting cloth bag. I was surprised by the weight of the first murre, and the strength of its wings – it was a relief to have it inside the bag where it couldn’t break free of my hands. As quickly as possible, we weighed it and began taking body measurements and taking feathers, blood, and fecal samples. All these samples were labeled, packaged, and sent to USGS and the University of Alaska, where they will be tested for disease, contaminants, sex, and even markers that can be used to show a broad picture of the bird’s diet.

Before releasing, Ann would tuck the murre’s head under one arm to show its legs and feet for banding, and once the metal band was shaped around its leg and the plastic bands were glued in place, the bird was ready to be released. I would take the bird from Ann, still in its cloth bag, and carry it to the camouflage netting. Ann had shown me the correct way to hold it, with my right hand over its back and my left hand holding its head, but, at first, I struggled to find the right place to put my right hand to keep the wings held down before the bird was ready to go. Eventually I figured out a system, leaving the bird in its bag until I was sitting next to the netting, taking it out and directing it in the right direction before I let it go. Approaching the netting was always daunting: even the sight of a person’s hand under the netting could alarm the rest of the colony, but the murres needed to be positioned so they could see the rest of the colony before they were released to stop them heading in the wrong direction.

Banding was an opportunity to get to know these murres. Their behavior, the way they interacted with each other, and with us as we were banding them. Each murre had individual characteristics that went beyond the slight differences in weight and bill length. Whether handling them during banding, or observing their behavior in the blind, it was fascinating to see how this community of individuals operated and responded to their environment. Capture and processing of each bird took about 15 mins, and their egg was usually left alone for that short period. But we also saw neighboring murres pull the egg over and tuck it up against their brood patch – a featherless area of warm skin on the lower stomach. Ann told us that murres often nest according to kinship, meaning that murres caring for neighboring eggs may be caring for their relatives.

While we spent the majority of our time with the murres, spending five days on Duck was also an opportunity to observe the ecology of the entire island. On evenings, if they aligned with low tide, we walked the perimeter of the island, counting puffins. Twice, we surveyed puffin nests, weighing and measuring the chicks, small, fluffy things still with their egg tooth. As well as puffin nests, we found smashed murre eggs among the boulders on the beach, speckled blue-gray shells dropped by gulls preying on the colony. There was always immense variation on the island, from low to high tide, in calm weather, or in rough weather. Even the puffins came to the island in cycles, sometimes with only a few solitary birds to be seen, and sometimes with so many in the sky and on the sea that it seemed impossible to count them. During our stay, the foliage of the island transformed, from summer green to the more battered brown of Alaskan fall. The days were getting shorter as well, there were sunsets now, in the late evenings, which often coincided with the times we would go down to wash our dishes at the beach.

We left the island at one of the lowest tides, carrying out our tents and equipment over twice the length of the beach we carried them up, but it was quick work, as Ann’s family showed up in force to help us schlep.

Many thanks to Ann for having us and to the murres for putting up with us!