A seabird is a bird that spends most of its life at sea.

Although all seabirds breed on land, they find their food out at sea, and many species spend 8-9 months a year totally out at sea and never touching land. Imagine that! Despite huge variation among different species, they are all adapted to life at sea. For example, many diving seabirds (like penguins) have dense bones to reduce buoyancy when they dive deep for food.

Seabirds also have specialized behavior to help them live and feed in the ocean. Seabirds have long lives (living as long as 20-60 years old). They also have fewer chicks (1-3) than other species of land birds. Living for a long time and having fewer chicks per year has likely evolved because of their unpredictable marine conditions, challenges of finding food at sea, and the relative lack of predation (animals that could eat their them and their eggs) compared to land-birds.

This fascinating group of birds is found from the tropics to both polar-regions, and some species of seabirds (like the puffins) are very familiar and well-loved by people all over the world.

More than 95% of the nation’s seabirds live in Alaska. Within Alaska, Cook Inlet stretches 180 miles from the Gulf of Alaska to Anchorage, and it is an important area for both breeding and wintering seabirds.

The Seabird Youth Network will be following a research project led by scientists from the USGS Alaska Science Center and Auk Ecological Consulting that is studying two very different species of seabirds on two islands in Cook Inlet. These studies help us understand how seabirds are responding to changes in our environment and provide information on the status and trends (patterns of increase and decrease in population numbers) of seabirds for management agencies, such as the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Common Murre (latin name is Uria aalge) is a beautiful chocolate and white-colored seabird closely related to the puffin. These amazing birds are built for diving, and can dive over 100 meters deep to catch their prey (mostly fish). Murres lay their single egg on rocky cliff ledges and island tops alongside many other murres. This photo by Sarah Schoen (USGS) shows an adult murre sitting on an unusual pointed-shaped egg (they incubate for about 33 days), and a large chick that looks almost ready to fledge (leave the island) at only two weeks old!

The Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) is a small gull species that also breeds on the cliff in dense colonies. Unlike the murres, kittiwakes delicately pick their prey (zooplankton and small fish) from the surface layers of the ocean, and they lay their eggs (1-3) in nests made of plants, sticks and mud. This photo taken by Sarah Schoen (USGS) shows a bird that has just caught a sand-lance (a long skinny fish species that is a common prey species for many seabirds).

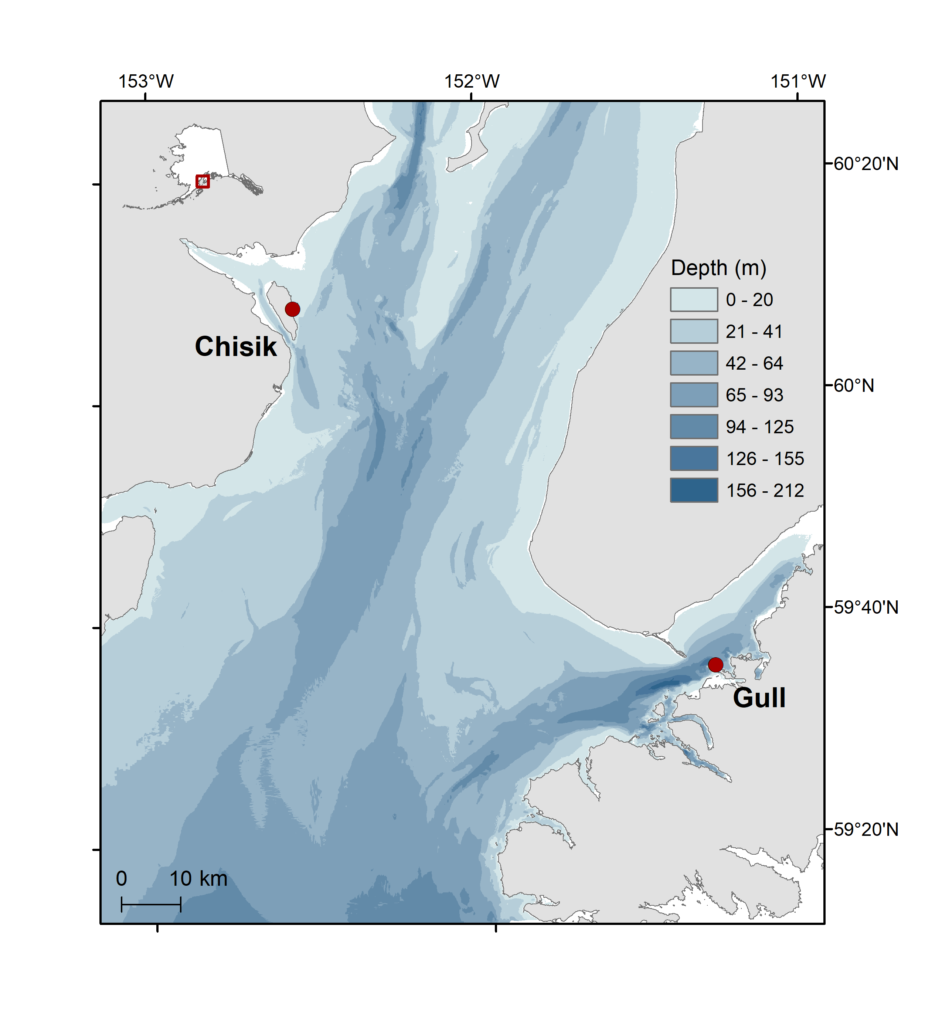

The below map shows the location of the two study colonies in Cook Inlet. Chisik Island is on the west coast of Cook Inlet, just south of Redoubt Volcano. Many thousand murres, kittiwakes and puffins breed on Chisik and the small neighboring rocky island called Duck Island. Chisik and Duck Island are surrounded by relatively warm estuarine waters (influenced by freshwater from rivers), and populations of seabirds have declined dramatically over the last few decades. The second seabird colony is Gull Island. Gull Island is in Kachemak Bay, just south of Homer, and the colony is close to relatively cool and highly productive waters. Although there have been signs of food stress in recent years, birds on Gull Island have historically had more food and are doing better than birds on Chisik/Duck Island.

Many seabird populations around the world have changed in numbers (increased or decreased) over time. Factors that affect seabird populations are often complicated, but are usually driven by changes in food supply. Seabirds rely entirely on the ocean for their food (small fish and zooplankton), and the availability of these prey (what they eat) is influenced by ocean conditions such as the temperature and salt content of the water.

Ocean conditions in Alaska have changed dramatically over the years, largely due to periods of warming and cooling in water temperature in the Pacific Ocean. In recent years, the temperature of water in the Pacific rose by 2-4° centigrade during the North Pacific Marine Heatwave (2014-2016). This was one of the planet’s most extreme marine heatwaves. In fact, scientists called it ‘the blob’ because it was simply so unexpected, widespread and confusing. The changes in the marine conditions associated with the heatwave have influenced the availability of food to seabirds, and signs of food stress following the North Pacific Marine Heatwave include population declines, breeding failures, and die-offs of seabirds.

Researchers with the Seabird and Forage Fish program at the USGS Alaska Science Center have been studying seabird populations and measuring the availability (species, size, density and distance from breeding colony) of their local food supply in Cook Inlet since 1995. This study has spanned both periods of ocean cooling and the recent North Pacific Marine Heatwave, and is providing valuable insight into how warmer ocean temperatures affect seabirds and their prey.

What the team is measuring at the colony? The team is measuring lots of different things! Including population size (counts of birds), breeding success (how many chicks do parents successfully rear), body condition, harmful algal bloom toxins, and adult survival (how many adults survive from one breeding season to the next). This photo by Ann Harding shows a field camp on Duck Island in 2023. Field workers camped for four days in July to study murres.

What the team is measuring at the colony? The team is measuring lots of different things! Including population size (counts of birds), breeding success (how many chicks do parents successfully rear), body condition, harmful algal bloom toxins, and adult survival (how many adults survive from one breeding season to the next). This photo by Ann Harding shows a field camp on Duck Island in 2023. Field workers camped for four days in July to study murres.

What is being measured at sea? The availability of seabird prey (what the birds eat) is determined both by the distance and density of prey species from the breeding colony, and the species of prey that is available. Some prey species have more nutritional value than others. The ship-based work uses hydroacoustics (study of sound in water) to measure the density of prey around each colony. Prey are also caught to measure size and nutritional value and confirm species identification. This photo taken by Sarah Schoen (USGS) is of the R/V Alaskan Gyre, the research ship used for the at-sea surveys in Cook Inlet.

What is being measured at sea? The availability of seabird prey (what the birds eat) is determined both by the distance and density of prey species from the breeding colony, and the species of prey that is available. Some prey species have more nutritional value than others. The ship-based work uses hydroacoustics (study of sound in water) to measure the density of prey around each colony. Prey are also caught to measure size and nutritional value and confirm species identification. This photo taken by Sarah Schoen (USGS) is of the R/V Alaskan Gyre, the research ship used for the at-sea surveys in Cook Inlet.

The Seabird Youth Network will be sharing stories about their field work in Cook Inlet, introducing the biologists who are doing this work, and learning what they are finding out through blog updates over the next year. The above photo by Sarah Schoen (USGS) shows some of the biologists collecting data on the R/V Alaskan Gyre. All blog posts covering this study will be under the Seabird Youth Network blog search category “Cook Inlet Seabird Studies”.