Mercury is one of the most toxic contaminants found in the environment.

It is released naturally during volcanic eruptions, however, over the last 300 years, humans have released lots of mercury into the environment while mining for gold and burning fossil fuels.

In fact, mercury concentrations found in arctic animals have increase ten fold!

Is mercury harmful?

Yes! In low concentrations, mercury can affect behavior of birds. For example, researchers working in Norway showed that male Black-legged Kittiwakes that had more mercury in their blood were less likely to raise more than one chick. Also, Black-legged Kittiwakes that skipped breeding in a season had more mercury than birds that did breed. In higher concentrations, mercury can change hormones that influence reproduction, and if concentrations are high enough, mercury can even kill otherwise healthy birds.

Seabirds and other marine predators accumulate mercury from their diet (fish, squid, crustaceans).

Zooplankton ingest mercury by eating food that includes molecules of mercury. Fish ingest mercury from eating these zooplankton, and seabirds then ingest the mercury from eating the fish that has eaten the zooplankton that has ingested the mercury!

The process of increasing amounts of mercury as you go up the food chain is called biomagnification, and leads to animals at the top (high trophic level) having much higher concentrations than animals at the bottom.

Mercury levels in Red-legged Kittiwakes

We have been collecting feather and blood samples from Red-legged Kittiwakes on St. George Island, to see whether mercury is present and (if it is) whether concentrations are high enough to cause these birds problems.

We sample both feathers and blood because they tell us two different things!

Blood tells us about mercury obtained through recent diet (previous 1-2 months), and feathers can tell us about the mercury levels that the bird accumulated during the winter.

Rachael Orben collecting a blood sample. Photo by Abram Fleishman

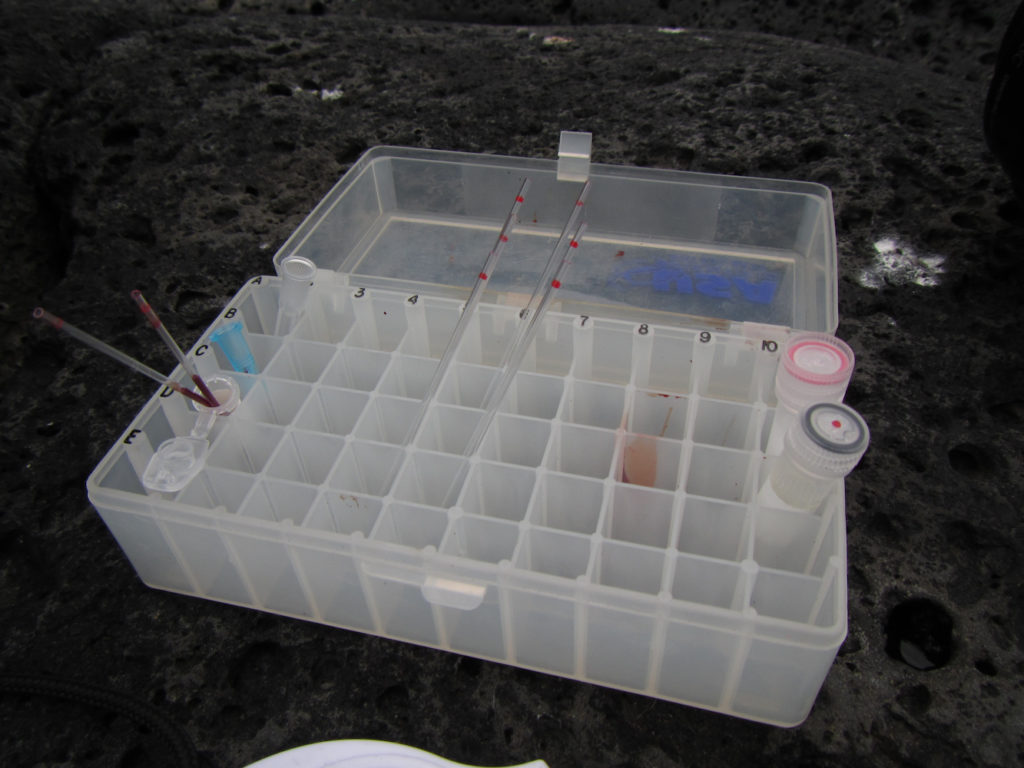

Blood samples are transferred to a vial. Photo by Abram Fleishman

To collect blood we prick the kittiwakes in a vein on the wing and collect the blood in a small capillary tube. The blood is transferred to a vial and frozen until it is analyzed back in a lab in California. Feathers are easier to collect.

Feathers are attached to a bird in a similar way as hair on a mammal, and you can pluck feathers from a bird in the same way as you can pull a hair off your head. We pull 6 feathers from the back of the head of each bird for mercury analysis. They are stored in a small bag and frozen until they are prepared for analysis.

Feather samples. Photo by Abram Fleishman

Feathers are washed and then dried in a special low temperature oven to prepare them for analysis. Once all the samples are prepared, they are brought to one of our collaborators (scientists in our team) Josh Ackerman. Josh works at the U.S. Geological Survey Dixon Field Station in California, and they have a special machine that determines the concentration of mercury in each sample.

What have we found out?

So far, we have processed all the samples from 2015 and 2016, and have found detectable concentrations of mercury in every single sample!

While every bird had some mercury, the concentrations are not very high (yay!), but they are as high or higher than concentrations found in other species where they have seen impacts.

We are analyzing the data to see whether mercury affects breeding or other behaviors.

We are asking questions such as: do males have more mercury than females? Does where a bird spends the winter influence how much mercury it has? And, does higher mercury levels lead to lower reproductive success (lower chance of laying an egg or fledging a chick)?

We are going to collect more data this summer. We will be returning to St. George at the end of May 2017, and stay until the end of June. We will catch some birds that have carried geolocation tags all winter long so we can see where they went, and we will sample their feathers and blood for mercury analysis.

text and photos by Abram Fleishman