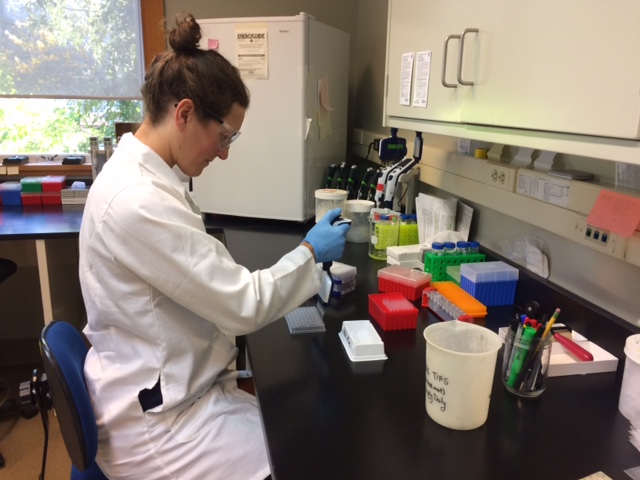

Graduate student Diana Baetscher (from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)) has been hard at work this past year.

Diana, her supervisor Dr. John Carlos Garza (NOAA/UCSC), and colleagues Drs. Eric Anderson and Kirsten Ruegg (UCSC), are part of a large collaboration studying fulmar genes to understand if fulmars caught as bycatch in North Pacific Groundfish fisheries can be traced back to the islands where they were born. Groundfish are fish that live near or on the bottom of the water, and include species such as halibut and cod.

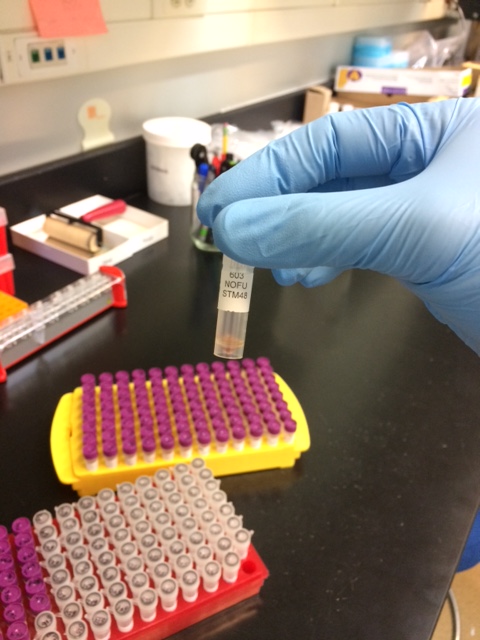

It is Diana’s job to put all the puzzle pieces together. As a geneticist on the project, she takes blood samples collected by biologists from the US Geological Survey from live birds on the four largest Northern Fulmar colonies in Alaska and extracts tiny amounts of DNA from each sample. Each sample contains the whole genome for each bird, which is a lot of information! In fact, a genome is more information than Diana and her colleagues need – what they want to find are short segments of DNA that are different in fulmars from each colony. These segments are useful genetic markers that the scientists can use to compare every bird they sample.

It is Diana’s job to put all the puzzle pieces together. As a geneticist on the project, she takes blood samples collected by biologists from the US Geological Survey from live birds on the four largest Northern Fulmar colonies in Alaska and extracts tiny amounts of DNA from each sample. Each sample contains the whole genome for each bird, which is a lot of information! In fact, a genome is more information than Diana and her colleagues need – what they want to find are short segments of DNA that are different in fulmars from each colony. These segments are useful genetic markers that the scientists can use to compare every bird they sample.

Diana digs through all of the genetic information and chooses the best 150 segments of DNA that might link the Northern Fulmars back to the island where they were born. She also tries to tell if fulmars breed on the islands they were born on, or if they breed elsewhere and mix their genes with the genes from birds from other islands. This is called population gene flow. Gene flow is the movement of genes among the breeding colonies. If birds stay on the island where they were born, and then breed there, then there is low gene flow. If the birds move around to different colonies to breed, then there is high gene flow.

Diana has been working to find genetic markers from colonies and to understand gene flow among the Alaska colonies of the Northern Fulmar. And she has some results!

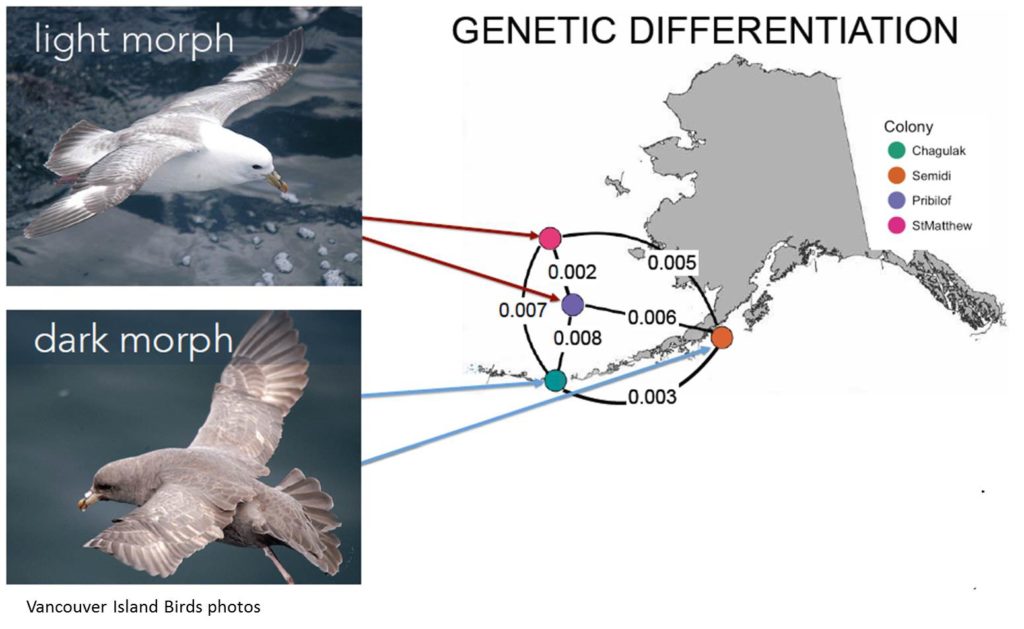

Diana and her colleagues analyzed gene flow between the islands and mapped it. In the map below, each island has a line drawn to the other islands with a number in the middle. This number is called the Fst number and refers to how different the genes are between the two sets of islands. When the numbers are low, it means that birds from the two islands touching the line breed a lot with each other. This is high gene flow. When the numbers on the lines are high, the fulmars breed more with fulmars on their home island. In other words, there is low gene flow.

See how the lines connecting the Pribilof Islands to St. Matthew and Hall Islands have low numbers on them? That means that fulmars from the Pribilofs often breed with birds from St. Matthew and Hall Islands. And guess what? The fulmars on these two sets of islands are whiter than birds from Chagulak and Semidi Islands, which have lots of fulmars breeding between them, but not very much gene flow with the Pribilofs or St. Matthew and Hall Islands.

Overall Diana and her team found more gene flow than they were expecting (maybe you noticed that all of the Fst numbers are very small!). But luckily, they still found genetic markers for each island. This will help the project move forward to the next step.

Next summer, Diana will work with Jessie Beck (Oikonos) to take samples from fulmars caught in the North Pacific groundfish fisheries and try to link the birds back to the islands they were born on. Maybe there will be a lot of birds from the Pribilofs. Or maybe a lot of birds from Chagulak. Or maybe the fisheries accidently caught birds from all the islands.

With their new information, hopefully the scientists can solve the genetic puzzle.